It is a forest, a mountain, a refuge, a place of religious practice and a setting befitting the tale of Beauty and the Beast. The air is a rare clean and fresh, like a gem of change from populated areas. Alas, there is no fairy tale half-human Beast, but there is beauty, captivating and calm. The rock formations are splendid, bold and old - there are several dome or columnar shaped pillars, formally referred to as Danxia. Volcanic activity long ago formed this contemporary landscape.

We embraced what truly the five elements in Chinese philosophy emphasised - Earth, Water, Fire, Metal and Wood. We felt close to Mother Earth; we soaked in her waters; we realised how fire moved mountains and provided warmth; we harnessed the use of metal, in our coaches, trains and other transport; and we saw the link between wood and where it all came from.

|

| Chinese Gooseberries or the Kiwi Fruits. |

The people work below the high places and some plant tea up the hills and cliff sides. A river ride reminds me of the Lord of the Rings. We walked and climbed till we tired out, feeling the body breathe better at night and with our leg muscles having the opportunity to restore and regrow. And to reach this dimension, we were seated on a high speed train from Xiamen North, that sort of carpeted us comfortably from the plains and coast, just three hours utilising latest modern transport technology, instead of taking over ten hours by road.

Western tales aside, the region also has its own legends - especially one tells of a struggling scholar, drinking excellent tea and using his robe to protect a much valued tea variety, the Da Hong Pao. In the past, this region was a favourite of retired or past court officials, who were taken by its surroundings and ambiance after a life in hectic and dangerous political circles.

The fauna in Wu Yi Shan remains mostly hidden, for sightings can be rare and on balance, perhaps better for the ecological and strategic survival of these mammals, insects and fish. We may have walked across the Pope's Spiny Toad, but fortunately not the Colubridae Bamboo snake. We would have been excited over seeing a goat antelope species called the Sumatran Serow and a black-backed Pheasant of the Chinese variety. There were butterflies in our bush walks (hopefully the Swallowtail variety called the Golden Kaiser-i-Hind).

There are endangered species of Clouded Leopards, hairy fronted Muntjac, South China Tiger or the Panthera Tigris Amoyensis and the North China Leopard. What I was looking forward to identify was David's Parrotbill but may be in reality, I was looking more to my steps up the rock stairs.

Straddling across two prefectures and two provinces in south eastern China, the Wu Yi Shan area is shared by Nanping Perfecture in Fujian and Shangrao City in Jiangxi Province.

We had the opportunity to stay in Wu YI Shan city of the Fujian side. With almost a hundred thousand hectares, the region is a UNESCO World Heritage Biosphere and Culture site that would appeal to the physically active, those wanting a temporary escape from urbanity and individuals who strongly bond with Nature. The high mountainous area is part of the Cathaysian geological fold system. Westerners used to refer to this region as the Bo Hea hills.

This is how we made sense of the large area - the River with Nine Bends, the Cliffs with Western Han Dynasty archaeological importance, the National Scenic Area and the National Reserve Area. Wu Yi Shan is the best representation of China's sub-tropical forests and has the most such biological diversity in one area in the whole of China. The rocks are Karst limestone, but how spectacular they are!

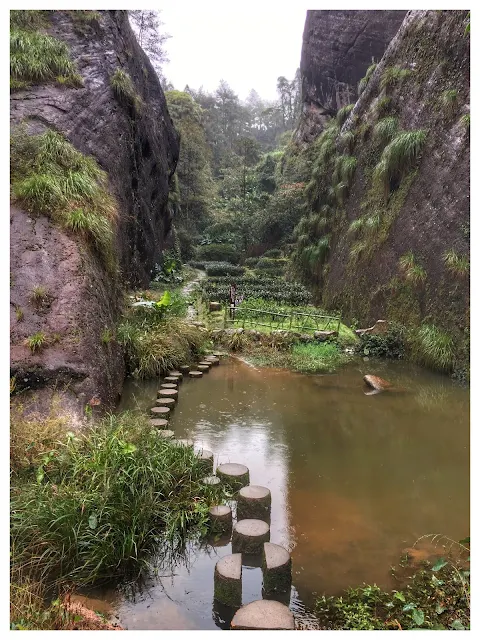

|

| The Da Hong Pao tea plantations. |

The reputation of the Da Hong Pao preceded our visit - and it has been for hundreds of years. Depending on who has informed you, the price per kilogram of this rich, bold and stand out flavour tea variety can range for 1000 to a million US Dollars. In the cold, single digit temperatures, even a sampling of such tea in a lower quality in a restaurant made me notice - it was no ordinary black Oolong and spoke of the rich volcanic soil and high altitude climate that nurtured its growth.

When my mates and I reached the peak of a trail in a plantation that grew such tea, we noticed how few bushes there were and how carefully they were taken care of. The tea bushes were nestled amongst cliff sides, fresh steams and a refreshing climate. It was raining constantly when we braved the climb but we were well rewarded at the top with this opportunity to embrace the best of Nature. I was reminded of when reaching certain locales, like a temple in the forest or a hidden waterfall in a valley, of the extraordinary vibes that all our personal senses fully relish - it is really like there is something in the air.

The Wu Yi Shan region is sandwiched by inland mountains and the coastal plains bordering the South China Sea, so it has a wet, rainy and cool climate. Many of these tea bushes go back a long way - Iron Arhat, Golden Turtle and White Cockscomb.

Another primary tea variety cultivated here is the Lapsang Souchong - a native of Wu Yi Shan, known in Mandarin as the Zheng Shan Xiao Zhong. It could be the first black tea in history.

The tea leaves here are smoked in a basket (called the Hong Long) over pinewood fires, originating from a military occupation practice during the Manchu Qing Dynasty. The fourth or fifth pick of tea leaves are used here, not the better quality first picks. This explains the need to enhance the aroma of such leaves by smoking them. Winston Churchill famously described this tea as "Mountains and Rivers Without End" and is perhaps the most favoured tea variety by Westerners.

With tea, come tea eggs! This fond Chinese practice of flavouring and infusing subtle flavours like tea on to hard boiled eggs can produce a light savoury and yet sweet experience for the palate. The Taiwanese are also fond of roasting ducks with tea leaves, although I did not see much of this in Wu Yi Shan town in Fujian.

Tea drinking can be ritualised in East Asia. The first cup drawn is to marry the water you choose to use with the tea leaves. You then release the primary flavour of the tea when you prepare a second cup. The unique soul and essence of the specific tea variety you use then comes forth with a subsequent cup. The process of preparing tea in Wu Yi Shan is labelled making Gong Fu tea. There are other important and subtle aspects of the tea preparation and drinking ceremony like the posture, the facial concentrations, the angle of the serve and more.

This culture of tea drinking is reinforced with other aspects of culture here in the monasteries, farming fields and a bonding with a nature based lifestyle.

Archaeological research and evidence show remains back four thousand years in Wu Yi Shan. The Wu Yi Palace was built here to conduct native ceremonies of sacrifice in the seventh century of the First Millennium. The Minyue Kingdom had its capital nearby, in the ancient city of Chengcun, during the Western Han Dynasty.

When Buddhism embedded in present day China, the philosophy and religious aspects were integrated in with the already significant presence of Taoism. This remarkable social-religious transformation is echoed through various places of worship here like the Wannian Palace, Sanqing Hall, Tianxin Temple, the Taoyuan Temple, Baiyun Temple and the Tiancheng Temple. Wu Yi Shan lists around sixty Taoist monasteries and places of worship plus 35 academies of learning from the Northern Song to the last dynasty, the Manchu Qing.

|

| Steamed egg for dinner down town. |

As autumn drew to a close and winter approached, the angle of light and the surroundings do vary from summer time.

We found ourselves waiting at bus stops under low light. We sought refuge from the rain in a rather Anglicised cafe, where the display of pastries and sandwiches befitted a contemporary cosmopolitan city area, but this was right some where in the reserve area. I found new respect for the powers, ability and inherent nature of bamboo, from which poles were used and crafted into a river raft, by which the six of us took an hour long leisurely cruise along the River of Nine Bends. We got over board with ordering KFC chicken in Wu Yi Shan Town in Fujian, when we arrived between meal hours and found ourselves hungry, with ten minutes to spare before a van driver took us to the reserve for the late afternoon.

|

| I enjoyed cappuccino here, with tasty sandwich like snacks. |

A rather interesting but understandable cultural requirement in Wu Yi Shan is the calling back to re-gather at a meal for married sisters and daughters on Leap Years. The responsibility falls on the shoulders of parents and brothers of the female relatives.

We all are aware of the family reunions on Lunar New Year Eve dinners, but this one singles out female members of a family, who realistically in the past in China do not get to see their birth relations for many years once they get hitched. It may not be the current scenario for many females in contemporary societies and in the cities, and modernisation has changed many old attitudes and practices. Ask even an overseas Chinese a simple question of whom they visit first to pay respects and love on the morning of the first day of the Lunar New Year. Is it the parents or the in-laws? Is it the family who mixes more, or the family who has more wealth and influence? Is the choice dictated by geographical proximity or do they take turns? What the parents of a young family actually do will influence the next generation.

|

| Boat man on the rafting cruise along the River with Nine Bends. |

Apart from cultivated tea, the natural flora in the Wu Yi Shan hark back to the Ice Age. Logically there are much of the coniferous forests, mixed or broad leaf; evergreen varieties that add to the beauty of the scenery; meadow Steppe biological growth; brushwood; and thriving bamboo plants.

The closeness to Nature and agriculture of its people in the Wu Yi Shan can be illustrated by some practices like the Mountain Call and Mountain Open ceremonies. Formal verbal urges for the tea bushes to continue to sprout and grow are essential components of such events.

|

| Entrance to cave trail leading to the Line in the Sky, an interesting crack of day light that comes through above you after you walk up a narrowing trail in the dark, inside a cave. |

The Big Impressions extravaganza at Wu Yi Shan, one of perhaps a dozen staged around significant tourist spots in China, but with different themes, was more than I expected.

The audience was literally moved around a giant and long stage, with spectacular plays of light over you that one may otherwise expect from a fireworks display. There is much use of technology and there is a cast of hundreds. So there we were, seated at around five degrees Celsius, soaking in with fascination about the legend of a scholar, tea picking and harvesting and the life of the folks by the river and up in the mountains. Lively singing accompanied the narration of gratefulness to Mother Earth for her blessings.

Boats sailed up a canal that just came alive for the show, projections of a flying horse were beamed across the real sky and I just could not figure out what was real and tangible from props and fleeting to the eye and heart. One of the best scenes in this 90 minute performance held outdoors was the tea leaf harvesting, pulsating with synchronised harmony and rhythm, amplifying countryside life and its various cycles. Another scenario staged was the pole pushing of bamboo crafts across the river. I often have the impression of China having so many people and doing things on a big scale - and this Wu Yi Shan tea picking opera said it all!

A holiday does involve effort in planning, but there are also sweet memories of what we encounter once we actually visit the destination. There was this brightly dressed woman, all by herself, standing on the shores of the River of Nine Bends. There was this human bottleneck trying to get to watch the Line in the Sky, all and each jammed up close physically beside limestone rocks in a darkened cave. There were steaming buns to start the day. I saw the need for no use of petrol to move along the river, only human ingenuity and labour. A hot pot meant more when the weather turned chilly outside. Little plastic slip-ons for feet became so useful when you did not want your shoes overly soaked.

|

| Karst limestone sights that make one ponder and awe about - this one was what the boat man especially pointed out to us. |

Getting around to the key sites within the Wu Yi Shan is not that hard. Visitors buy a multi-entry pass to the huge dedicated reserve and once you arrive at the entrance, you walk a short distance before jumping on to any of the medium sized coaches that can drop you at various key points for drop off.

Robert Fortune was a colonial official in the late 1840s who reached Wu Yi Shan in the pursuit of commercial interests of the British East India Company to source tea plantations, varieties and flavours. Robert disguised himself as a Mandarin and successfully broke the very important monopoly then held by China on tea production and exporting.

The rest is history and continued to feed the frenzied demand for tea drinking in British social life. Fortune resolved the serious issue of a trade imbalance that already occurred between China and a Western nation.

In the tradition of adventurers and colonists in the age of seeking trade, wealth and fortune, many varieties of so-called native plants from around the world were uprooted to other lands (mostly other European controlled colonies) for cultivation - I can think of cocoa, rubber, chillies, oil palm, pepper and wheat.

|

| Rafting on the river with Nine Bends. |

No comments:

Post a Comment